I mentioned sustainable performance in a previous post, telling that it “could be a blog post on its own”, and after noting interest on the matter from people I highly respect, I decided to write this post.

What is sustainable performance?

If you worked as a software engineer for some time, you must have faced at least once the question: “is my code running at its full potential?”.

So many intricacies can arise from such a simple question, especially in a highly dynamic industry such as Information Technology. How do you define what full potential means? Great user experience? Maximum theoretical throughput?

What can be changed to improve the status quo? Switch to a different algorithm or data structure? Change the compiler? Run on different hardware? Should we apply any of these actions, what effects are we going to produce?

Here is where sustainable performance can help.

Sustainable performance is a methodology to create software systems that are good enough for users, while minimizing their impact on the environment.

“Good enough for users” means that the systems respect quantitative measures of quality, as it delivers all the expected features to its consumers. “Impact on the environment” is what any software will cause eventually, depleting some Earth resources through the machines it runs on. It will do so directly, by consuming more electricity in existing machines, or indirectly, requiring more rare-earth minerals to build new machines to increase datacenters’ capacity.

At its core, sustainable performance is an iterative, finite set of steps that will ensure your systems deliver what is expected, while keeping under control the consumed resources. It provides actionable items that you can apply to any codebase and infrastructure to develop and run more earth-friendly software.

The methodology is influenced both by my previous experiences in operations and my more recent software engineering career, working on a continuous-profiling tool with an amazing group of people.

The need for sustainable performance

Software has eaten the world. There is nothing in today’s civilized world that is not in contact with a piece of software.

In an increasingly digital world, the creation and utilization of software continue to grow at an exponential rate. However, this rapid expansion poses a challenge in terms of the environmental impact caused by the growing need for computing resources. As we strive for technological advancements, it becomes imperative to develop more efficient software that optimizes resource utilization, reduces energy consumption, and minimizes carbon footprint.

Wherever our systems are deployed, either it be a public Cloud datacenter, or a machine in your home laboratory, we should always try to do more with less.

By building performant and efficient systems, we can be one step closer to better environment-friendly software.

The goal of sustainable performance

Note that throughout the post, we will never mention the word sustainability alone: this is intentional.

We should not conflate sustainable performance with sustainability programs: carbon-neutrality is great, but it’s not the right point to build upon if we want to improve the status quo.

Sustainability programs have the goal of offsetting carbon emissions caused by datacenters with CO2 credits, collected either by purchasing them on an open market, or by performing activities that will somehow compensate CO2 production. While this is a great intent, it surely does not scale as well as avoiding CO2 emissions in the first place.

A sloppy workload running in a datacenter that offsets part or all of its CO2 emissions is only partially helping in building a more sustainable future. We need to face the reality that only by changing how systems operate internally we can create long-term, sustainable habits for our system to operate and grow at planet scale.

How to get started

Performance and efficiency should not be the end goal of any software craft, especially when creating a new system from scratch. They become essential though when we want to scale up the business powered by said software.

We should try to introduce as soon as possible Service Level Objectives in our products, with a clear focus on measuring the quality of users’ interaction with our products through our systems.

We need a way to understand if we’re creating systems that serve their purpose before improving them.

In this, SLOs and SLIs are a great tool to detect if we are respecting our users’ expectations. Adopting SLOs allows quantifying how the product is delivering its business logic, so you can then validate that the changes you are introducing to improve systems performance are not degrading the quality of the product.

ROSTI drives sustainable performance

I am afraid that potatoes, eggs and bacon are not involved here.

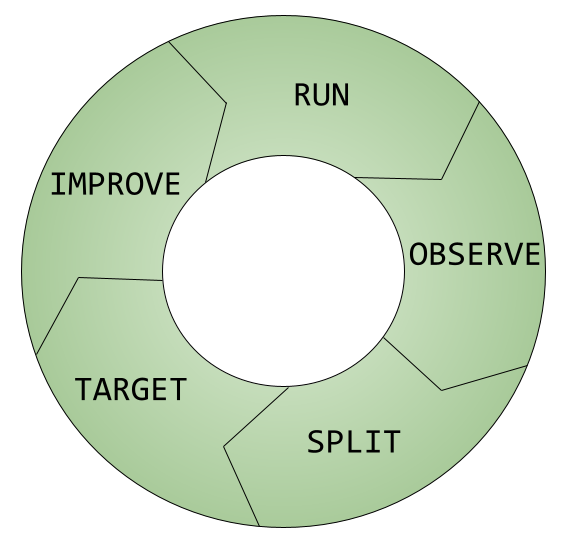

Rösti is not only a very popular Swiss dish, it’s also the acronym I use to remember the 5 steps to follow to achieve sustainable performance:

- Run

- Observe

- Split

- Target

- Improve

Below, I present each stage with an example list of practical items that will help your system be more sustainable-performant. The list does not pretend to be exhaustive at all, and I am sure anyone can add more items with their own area of expertise or specific placement in the industry.

At each stage, we can assess our maturity and understand if we need to take action to change some parts of the system so that the next phases will be possible.

There are no strict criteria of validation for a stage to be called successful: similarly to most modern methodologies, setting a good cadence is more important than the actual results obtained at each iteration. Thus, prefer multiple short ROSTI iterations over a long, “perfection-achieving” redesign of the system. The first way is proven to be better in the long run, as practicing multiple times improves the quality of results. The latter is not only impractical, it is often impossible to achieve.

Run

The initial step is to run the software and collect key performance metrics while exercising its functionalities. This involves executing the application under realistic conditions to assess its current performance levels, while collecting data on how the software executes.

You may be running a production environment with a real user base that consumes your applications, or you may be testing in an isolated environment a new system that works transparently for the average human; it really doesn’t matter. The important thing is that you should see something run first, and then proceed in making it better.

“Premature optimization is the root of all evil”—you heard this one already. It’s true.

- Deploy your system to any infrastructure as a starting point

- If possible, adopt Canary Releases or other Continuous Delivery practices such as Progressive Delivery, so you can iterate with speed and safety and experiment in production with small, frequent changes

- Understand if the facilities where you are running it provide telemetry:

- Cloud provider with native monitoring APIs

- Operative system with granular telemetry data

- Libraries and dependencies that provide statistics on their internals or a way to hook into them

- Exercise the system with synthetic data if necessary

- Collect disparate sets of metrics that will let you know how your system behaves under various conditions:

- Spot tail latencies, flag them if they are recurring issues

- Take note of possible failure modes and verify if you can detect their behavior

Observe

With a continuously-running system, we can now observe what it does during its evolution. We should focus on understanding the behavior of the system, how it varies when exposed to different conditions, identifying performance bottlenecks and areas of inefficiency.

The scope of this stage is to understand if the data we are gathering can help us pinpoint specific parts of the codebase or system configurations that contribute to suboptimal performance. We are not hunting down improvements just yet, we need to be absolutely sure that we can do it first.

Carefully analyze the gathered data, try to make sense of the information gathered from different sources to form a complete view of the system’s behavior. “Complete” means that you want to be able to dissect how the system behaves both North-South (e.g. from users requests to a database connection) and East-West (between same-level, interconnected components). At the same time, you want to be able to look at macro-aggregated data as well as introspect specific components' behavior.

- Review metrics aggregation rules: are we losing too much information? Or are we keeping unnecessary data?

- Add ad-hoc telemetry to sensible components: if you are inspecting a database, you may want to gather more data on disk usage than when you are working on a graphic design application.

- Write benchmark tests and use micro-benchmarks during development to spot areas of improvement across the codebase

- If you are working with networked applications or a microservice architecture, adopt distributed tracing: OpenTelemetry, AWS X-ray, Zipkin, etc…

- Adopt profiling tools when iterating on code during development, to understand how various implementations can differ

in

execution or

resource usage:

perfon Linux,async-profilerfor JVM,pproffor Go, Intel VTune etc… - Adopt a continuous profiling tool in production, to be able to collect fine-grained data about what applications are the most resource intensive and how they change over time: Universal Profiling, Parca, Pyroscope, etc…

Disclaimer: I work in the team building Universal Profiling, one of the tools mentioned above. This post is not meant to advertise it over other continuous profiling solutions.

Split

In the split phase, the goal is to isolate the performance issues into distinct components or modules within the system. This process enables focused analysis and targeted optimization efforts on specific areas, ensuring a more efficient and effective approach to performance improvement.

The most sensible approach to gain improvements is “divide and conquer”: don’t expect to achieve huge gains all at once, but rather segregate the problematic parts of your software into logical units that can be tackled in isolation.

- Identify low-hanging fruits: these are typically very small, but frequent, units of execution. For example, if you are developing a chat application, likely the most common operation is to broadcast a message from one to multiple users

- Detect patterns across applications or components that refer to a unique source (e.g. a shared library)

- Have a clear understanding if a subsystem is being “slow” and/or “inefficient”: when defining boundaries, it’s important to determine if you have saturated I/O, CPU, or both! The tools that you use to observe should be telling you. Use the information at your disposal to detect where to cut the boundary of your investigation.

Target

With a clear understanding of the segregated components, the next step is to establish performance targets in the form of performance SLOs for specific components. Setting these targets provides a quantifiable benchmark to aim for during the optimization process.

It is important to note a key aspect: performance improvements must honor a two-fold commitment. On one hand, they free up some CPU cycles or disk/RAM usage, making room for other parts of the business to grow and scale more seamlessly. On the other hand, they must respect the existing business purpose of the system.

You should already have defined SLOs in terms of availability over a month, error rate threshold, or any other business metric.

Now we need to define performance targets. We can call these targets Service Performance Objectives, or SPOs in short. Their purpose is to improve the system’s efficiency while keeping existing SLOs in place, thus retaining all the business value currently provided, but reducing the consumption of resources.

Similarly to how SLOs are built upon SLIs, we will create Service Performance Indicators (SPI): using the data collected from our systems, we will create quantitative measures of how the system is performing in a certain area. The SPI will target only one of the components individuated in the “Split” phase. Each SPO will refer to a single SPI in its definition.

- Review the list of existing SLIs, detect if some of them are already indicative of performance-related metrics

- Build SPIs to track down the performance behavior of the system

- Create SPOs on top of existing SLOs

- Communicate the existence of the SPOs and your commitment to fulfill them

For example, if we want to create an SPO for a cache service deployed at a video streaming website, we may want to

track the SPI “total cache memory usage over requests per second”.

We then go ahead and define a threshold for the SPI, say it’s 123.

The SPO will then be defined as

keep the “total cache memory usage over requests per second” SLI below 123 for 95% of the time over a month

Just like SLOs, the time period for which you perform the measurement can vary.

Common SPI/SPO definitions we could be using:

- P95 latency of RPC “xyz” should be lower than 5 seconds, for 99.9% of each month (this SPOs could be a “subsection” of an existing SLO)

- keep the CPU throttled time for a given application below 5%, for 99% of each week (applies mostly to containerized workloads)

- keep the percentage of swapped memory pages below 5% of total mapped pages, for 99% of each month (likely suited for a stateful service)

- use no more than 5 GB of ephemeral disk for each replica of service X, for 99% of the month

Note: in the first ROSTI iteration, you can size the SPOs almost arbitrarily, and it’s usually better to start with relaxed SPI thresholds. It is crucial that once set, you never make pejorative adjustments to SPOs: you always have room to make them more challenging when further improving the system.

Improve

You may be thinking: “Finally! This is where it gets interesting”. Please think twice. The improvement phase is equally important as the previous ones, not more important.

The first time running a ROSTI, the previous phases are actually more important as they will likely require a more thought-through process and a bigger effort to be set in place. We won’t be able to make a system better if we don’t know what to improve, and which data we need to validate our assumptions.

In this last phase, we are going to analyze all the segregated components and explore several possibilities of improving their status. This may include code optimizations, resource utilization enhancements, architectural changes, or any other optimization techniques.

Start with a single component and a single SPO: what can you do to reduce overall CPU usage, reduce overall memory consumption, avoid resource contentions, and so on? The goals of the “Improve” phase are two:

- find an implementation of your component that preserves the SLOs while allowing a reduction of the SPO(s)

- re-evaluate the SPO’s threshold with the new implementation, consider if they can be reduced for the next ROSTI

Below a list of common actions to improve your systems.

-

Review the architecture: sometimes, an external service could be a shared library—you may replace an expensive network call with a more efficient CPU context switch

-

Code optimizations (in order of efficacy in my experience):

- find a more efficient replacement for third party libraries, e.g. more efficient serialization/deserialization, or less allocation-prone local caches (e.g. pola.rs instead of pandas)

- switch an algorithm or a data structure to a more efficient implementation, or an implementation that is proven to be executing better for your data set or type of workload

- understand and improve concurrency and threading models inside your software: lock contention, memory thrashing, and CPU cache coherence issues are the most common causes of suboptimal throughput; you can solve them with more careful handling of concurrency and parallelism in your programs

- vectorization and SIMD: validate that you’re actually making the most out of your CPUs, verify the runtime or machine code is leveraging modern CPU features

-

Resource consumption optimizations:

- validate logging calls and their levels across your applications

- update the runtime, update or switch the compiler/interpreter: there are various JDK distributions,

- switch CPU architecture—in my previous post, I detected how for one of my Lambda functions, I could get a 20% latency reduction just by recompiling and running it on ARM instead of x86

- review and reduce heap allocations inside a specific component, verify the garbage collector metrics (when there is a GC)

- tune the runtime/interpreter for specific workloads, e.g. setting soft memory limits or a maximum number of threads

-

Infrastructure/architecture optimizations:

- check for duplicate processing of the same data across multiple components: by far the best improvement you can achieve, but also one of the most difficult to detect

- schedule workloads on appropriate hardware, e.g. using Kubernetes node pools with taints and tolerations, or pod affinity and anti-affinity to avoid resource contention across CPU/memory-bound applications

- detect and remove underused storage, understand if garbage data (e.g. temporary files) that could be evicted is being kept

Remember: all the improvements above should be introduced only with the promise of not creating a disservice to users. There may be situations where a huge performance gain is changing the functionality of a product. As an Engineer, the prospect of delivering such improvement is exciting. But before rolling out such a change to production, you must discuss if it is tolerable for the business to incur into a functional change of the system, even if it can achieve an amazing performance boost.

As an example: consider improving a search application for an e-commerce product: with some changes, you manage to cut the P95 latency into half, but without preserving the expected ordering of items. This change impacts the business, because items’ ordering contributes to revenues. The efficiency improvement in itself is great, but cannot be adopted because it is unsuited for the system.

Be conscious that the goal is optimizing the system, reduce its environmental and monetary cost while keeping the exact same functionalities. As already mentioned: prefer small iterations, little gains can compound drastically over time.

Wrap around

When you have introduced an improvement in your system, you go back to the “Run” phase. And the cycle repeats: you make a new ROSTI, where you may be creating a new SPO, or trying to work on an existing one by making it more challenging.

It is up to each organization to decide if the cycles should be continuous or have a regular cadence. It is often better to set a cadence prior to start any iteration. Setting quarterly or bi-monthly periods may be a good habit to start with.

Conclusion

Running and operating efficient software is crucial in a world where software creation is increasing exponentially. The ever-growing need for computing resources poses a danger to the climate due to energy consumption and consequent carbon emissions.

Adopting methodologies like ROSTI can be helpful to mitigate the environmental impact of computing resources, and it can be fun too! By focusing on reducing CPU consumption, optimizing code, managing resources efficiently, and continuously improving systems’ performance, we can create more sustainable and eco-friendly software systems.

In addition to the environmental benefits, efficient software also offers tangible advantages such as improved user experience, reduced costs, and increased scalability. By optimizing software efficiency, we can build applications that not only delight our users but also contribute to a more sustainable digital ecosystem.

By embracing the ROSTI methodology and incorporating the aforementioned techniques, IT practitioners can play a vital role in reducing the environmental impact of software systems while delivering high-performance applications.

I think it is imperative that we prioritize sustainable performance to ensure a greener and more efficient future on Earth.

Related projects to watch

- Kepler: very cool ecosystem to improve performance of applications running on Kubernetes

- Green Software Foundation

- OpenCost cloud-native cost allocation tool

Special thanks

Thank you 🙏 to Sean Heelan and Tommaso Preverio for reviewing the draft of this post and providing feedback.